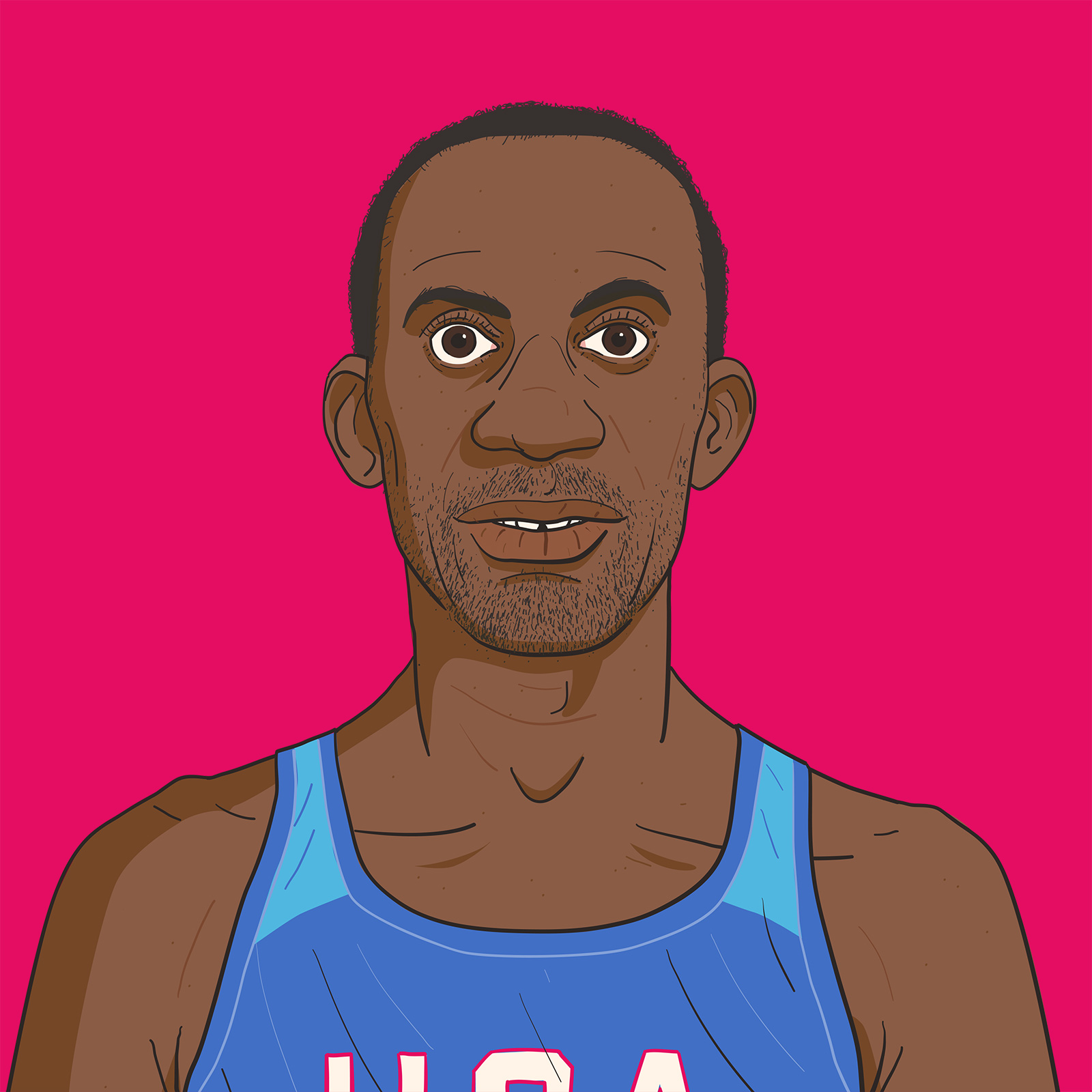

Lex Gillette is a blind Paralympics champion in the long jump category. He started losing his sight aged seven and despite ten different surgeries at the age of eight doctors told him there was nothing they could do. At school his coach introduced him to long jump, which he excelled at, collecting medals at all levels. He is the current world record holder in this field. He won the gold medal for long jump in the last Paralympics championship, which was in 2019 in Dubai. He’s also a motivational speaker and a singer-songwriter.

Lex talked to Aleks about the challenge of adjusting to his circumstances at such a young age, the encouragement he received from his mother to maintain his independence, and about the process he uses to navigate the world and his chosen sport. He also talked about an inspirational pastor whose YouTube videos help him keep focus on his training and his writing.

Transcript

Lex Gillette:

As I move through life right now, places that I am very familiar with, I have vivid images of those places and things in my mind, which allows me to be able to move and navigate very freely, because I have this vision, and that allows me to just be very confident and bold and intentional in my actions and movement. So when you talk about sport and being introduced to long jumps, something that out of all of the sports, it’s like, “Wow, okay. The blind guy chooses to run as fast as he can and throw himself in the air. Wow.”

Aleks Krotoski:

Hello. You are listening to Standing on the Shoulders, a podcast in which inspiring people tell us about their giants, the people whose metaphorical shoulders they stand on. Across these episodes, you will hear the stories of a number of thinkers and innovators, visionaries who steer clear of the well-trodden paths and build their own fantastical world instead. They’ll tell us about the key moments that shaped their professional journeys, and they’ll talk about the single most meaningful person to inspire them along the way. Hosted by me, Aleks Krotoski, and supported by Pearson.

Aleks Krotoski:

Our guest today is Lex Gillette.

Lex Gillette:

And I am a Paralympic athlete competing for Team USA. I am currently in Chula Vista, California, which is about 20 minutes south of downtown San Diego.

Aleks Krotoski:

Lex is a blind Paralympics champion in the long jump category. He is the current world record holder in this field. He won the gold medal for long jump in the last Paralympics championship, which was in 2019 in Dubai. He’s also a motivational speaker and a singer-songwriter. Lex grew up in Raleigh, North Carolina.

Lex Gillette:

I had a really good childhood, I would say. Prior to me losing my sight, I was very active kid. My mom and I pretty much, it was the two of us, my mom’s a single parent. And she had me involved in a lot of different activities. I played recreational baseball and I learned how to swim. I wasn’t swimming competitively, but I took lessons and I could hold my own in the pool and run and do the cannonballs and all that other stuff into the water. My mom, she would take me to the park and we walked a lot of places. My mom is visually impaired also. And then I experienced sight loss at an early age. I had actually come home from school, and that night, that’s when I started noticing that I was losing my sight randomly out of the blue.

Aleks Krotoski:

How old were you?

Lex Gillette:

I think at that particular time I was seven.

Aleks Krotoski:

Just a little fellow.

Lex Gillette:

Yeah.

Aleks Krotoski:

Do you remember what it was that you couldn’t see? I mean, I don’t know what the nature of your sight loss and the degeneration, how quickly it happened or even what it looked like.

Lex Gillette:

It was, lights are blurry, hard to see my reflection in the mirror. Things were looking faint. They were looking blurry. They were in a lot of ways disfigured a little bit. And the next day we went to the doctor and after an examination, the said I needed to have an emergency operation because I was suffering from retina detachments.

Aleks Krotoski:

I’ve heard stories of retinal detachments and how terrifying they are just simply because it happens so fast, and it’s painless, isn’t it? It’s not a painful experience.

Lex Gillette:

Right. Yeah. So a total flip of a light switch, if you will. Everything looks fine one minute, and then a few minutes later, it’s like, “Man, this is totally different.”

Aleks Krotoski:

Once you noticed it, was it back and forth?

Lex Gillette:

It was a gradual decrease. So I want to say from that point up until I was basically eight years old, over the next year, I had 10 operations to try to fix the issue. And it was go in, everything would be fine. The operations seemed successful. I will be able to see for three to four weeks or so. And after that time, my sight would get blurry again. And each time it would get worse than the time before, in terms of excruciating. I think the first one, two, three, four maybe operations, you’re pretty optimistic in thinking that it’s going to work and you’re going to be able to see clearly again, and you won’t have to worry about going to the doctor any more. And then you get to the latter part of the ten: eight, nine, ten, and I think that I had subconsciously gotten to the point where, “All right, this is going to be reality and I might need to figure out what’s going to be next. How are we going to do this?” And then after the tenth one, the doctors confirmed that with, “Hey, there’s nothing else we can do. The likelihood of you being blind is pretty high.”

Aleks Krotoski:

That’s heavy for a seven, eight-year-old. But also there’s something else that’s going on at that time, which is you’re becoming a social creature, right? And all of this going into surgery and coming out and recovery and all of that kind of thing is disrupting your social life.

Lex Gillette:

Oh man, that’s a really good question. I think the challenge at that time is trying to make that transition, because yeah, can you prepare for those types of things? Because again, to your point, you’re trying to figure out life at that time. You’re making friends, and the average kid, probably isn’t dealing with something like the magnitude of losing their sight. So they’re just trying to learn and learn about their friends and your environment and how to navigate and traverse through life.

Aleks Krotoski:

Gradually, Lex says he just got used to this new reality, and so did his friends and his cousins. They were empathetic about it, and naturally a little curious, but they didn’t treat him any differently. They always included him in their adventures. Soon Lex learned to visualize things around him. He would assemble a scratchpad image of his environment to be able to get safely around. He ran outside, he built a tree house. He even learned to roller-skate. And throughout, his mother was a crucial source of support.

Lex Gillette:

One of the stories I love to hear my mom talk about is she said that she was in our living room and she was praying or meditating. And I run up to her and I tap her. I say, “Mom, mom, mom, I need to learn how to read dots.” And she says that when I had told her that, at that point, it was “Okay, this is confirmation that my son understands it. He gets it and knows that this is life. This is reality. This is the path that we’re going to go down.” And from there, it was her being able to get out there and do everything possible to make sure that I would have everything I would need to be independent and self-sufficient moving forward.

Aleks Krotoski:

Go single mama. Incredible. When did you realize your mother was so fierce?

Lex Gillette:

Well, once I got to the age where I really understood what was going on, I knew that there were these IEP meetings, Individualized Education Plans. And so in these IEP meetings, my mom, she would go in there, and I’m pretty sure there were many times where she had to fight tooth and nail to ensure that I got this piece of technology, or I had this book in braille, or I had teachers who were going to set the same standards and expectations that she did. I think that she was relentless in that fact, and was very much, “Listen, this is the environment and the atmosphere that he resides in when he’s here at my house, and I want this to be consistent across the board.”

Aleks Krotoski:

Sport is an incredibly physical thing, and especially the kind of thing that you’re doing, where you are running hell for leather in that direction and you can’t see. So can you talk a little bit about the experience of learning what your body did and your boundaries were and whether sport was part of that renegotiation?

Lex Gillette:

The beauty of my situation is that I was active prior to losing my sight. And after I finally actually went blind, it was a matter of me becoming comfortable again with moving around. And I had my mom and a number of individuals who helped me to regain that confidence to get back out there and run and jump and roll around in the grass and all of those things. My mom, she was never the type of person where if I was doing flips outside, then she wasn’t saying, “Oh no, you need to stop that.” She would in a lot of ways encourage it and say, “Hey, there you go. Keep working, keep exploring, keep discovering.” And now I can say, “Keep learning: learning about yourself, learning about your environment.”

Lex Gillette:

I mean, I’m thinking about right now, the neighborhood where I grew up, the neighborhood that I was last able to see. If we were to go back there right now, I would be able to take you on a first-hand best tour of the neighborhood. Assuming that nothing has changed, I’ll be able to show you absolutely everything, because that environment, that neighborhood is seared into my mind. I remember where the three steps were that led to the sidewalk to our house. I remember the five or six steps that it took to get up to the actual front door. I remember what the apartment looks like. There was a ledge in front of our apartment building that led to a small grassy area. I would be able to take you through all of those scenes, those events, those places, and it never has left.

Lex Gillette:

And so as I move through life right now, places that I am very familiar with, I have vivid images of those places and things in my mind, which allows me to be able to move and navigate very freely, because I have this vision, and that allows me to just be very confident and bold and intentional in my actions and movement. So when you talk about sport and being introduced to long jump, something that out of all of the sports, it’s like, “Wow, okay. The blind guy chooses to run as fast as he can and throw himself in the air. Wow.” When you think about that type of sport, I’ve used those same skills that I learned at an early age, tapping into my spatial awareness and the proprioception.

Aleks Krotoski:

Growing up, Lex loved sports, especially basketball. He would listen to games on the radio and he would dream of leaping like Michael Jordan, but his life as a student athlete found him by accident. One day when he was 14, he and his classmates had to do a standing long jump as part of a fitness test, and he beat everybody. This feeling was invigorating. He actually beat his classmates who could see. So he joined the school track team. Two years after he graduated from high school, Lex took part in his first international event in Quebec in Canada. Throughout his training, he was supported by a loyal coach and a trustworthy team. They became his eyes and his ears. They were his visual scratchpad. They helped him to see what was around him in an international arena when there are thousands of people watching and screaming from the stands.

Lex Gillette:

I have my coach or my guide, who they give me that same type of layout of what the environment is, how long the runway is, how wide it is, where the takeoff point is, how far the takeoff point is actually away from the sand pit, how long the sand pit is, how wide the sand pit is. And we’re essentially going through a lot of the same steps that I would go through as a child. And it again, creates this visual, this image inside of my mind, so that, “Hey, I feel comfortable, I feel confident, and I’m able to be incredibly intentional in my action in that space.” Because in a lot of ways, it’s like I can actually see what’s going on.

Aleks Krotoski:

You are literally just going faster than most people can actually run, frankly. Can you recall what the feeling is when you are doing that, or I suppose more likely when you did it for the first time and you realized no harm would come and it was like, “Well, duh, this is what I’m going to do. This feels amazing.”

Lex Gillette:

I think the feeling was… As you can imagine, the first portion of that is, you try it for the first time. It’s scary. You have a little bit of trust that you’re trying to work through in terms of trusting the person who’s clapping and yelling for you. And then there’s that layer of trust that deals with you: you actually getting to the point where you can trust yourself. Once I got to the point where I was super comfortable and I was like, “Oh, this is fun. This is what I want to do,” it transformed into a freedom of sorts. It was something that I could do. I realized that I was good at it. And there was no one in the world who could tell me that, “Oh, you’re not able to do this.”

Aleks Krotoski:

That confidence helped Lex rack up a number of big wins over the next few years, and by 2011, he was also triple jumping. He won the bronze medal for it at the IPC athletics world championships in Christchurch in New Zealand, and later that year at another championship meet in Mesa, Arizona, he won the gold medal for the long jump and set a new world record. In the course of all of this, Lex became the first blind athlete to ever long jump beyond the 22-foot barrier.

Lex Gillette:

I knew that I had built a confidence in my mind that, “Listen, it really doesn’t matter what anyone else says. I know that this is what I can do. Who cares what the other people may say? I’m going to go out here and prove you wrong.” But I think more than anything, I’m going to prove myself right. I know what I’m capable of doing. I have an image of myself that you’re not going to ruin that for me because this is who I know I am. This is who I know I can be

Aleks Krotoski:

The year 2012 really tested Lex’s confidence. He was injured a couple of weeks just before a crucial event in Canada. It was his first significant injury, but he managed to overcome his doubts and he won a silver medal in the Paralympic games in London in England. The next year he won another gold medal at the world championships in Lyon in France.

Lex Gillette:

Gravity is a law of nature. But when you think about people’s expectations and how they view you and the biases and things like that, that’s the gravitational pull figuratively speaking. And when I’m jumping, no one’s holding me down. No one’s pulling me back. I’m soaring over all of that.

Aleks Krotoski:

How do you balance that self-confidence, with, “Hey, I know what I’m doing and I trust myself to make the right decisions,” with other people saying, “You shouldn’t be doing it like that,” or, “You need to be doing it like this.” How does that battle look within yourself?

Lex Gillette:

It’s just a matter of building your circle, knowing who’s in your circle and acknowledging the fact that, “Hey, there’s a lot of things that I know and I’m confident in, but there are a lot of things that I don’t know as well.” But that’s why I have my coach. That’s why I have a strength and conditioning coach and dietician and all of these other people. And you literally have to lean on them.

Aleks Krotoski:

But sometimes things just go wrong. In 2015 on a world championship in Doha, Lex leaped and ended up sprawled on the side of the pit. His tights were ripped up. His elbow was mashed up. And usually his guide Wesley claps when Lex is running towards the pit to let them know when it’s safe to leap, but this time the claps echoed in the stadium, or maybe they just got drowned out by the noise of the crowd. Lex thought that he had missed a shot, but it turns out he had one more try. So he jumped and ended up winning the gold medal.

Aleks Krotoski:

What happens? How do you know when you’ve made a mistake? You suggested that, okay, if you found a team member who isn’t right, how do you deal with… I know for myself, I’m terrible at that. I will hold on to a bad decision just because it’s almost inertia is going to keep me there rather than just being like, “No, I’m going to stop this now and I’m going to move forward.” Where are you in that continuum?

Lex Gillette:

It’s hard. It’s definitely hard. A lot of it stems from, at least for me, is you don’t want to hurt anybody’s feelings or make them feel like they’re inadequate or make them feel as though the work that they’ve done has been not as good or not as useful. So building up the courage to just be open and honest is very important. Being vulnerable, that’s huge. And I think that in a lot of ways too, if you built your circle up in a way that these are individuals who genuinely care for you, when you’re vulnerable and you put your thoughts and ideas out there, I think it also gives those around you permission to do the same.

Aleks Krotoski:

This approach is clearly paying off. In 2019 at the World Paralympics Championship in Dubai, Lex won yet another gold medal and he broke a 17-year championship record.

Aleks Krotoski:

Do you have any thoughts on what will replace the role of sport in your life? You’ve been an athlete, a professional athlete for a long time. And it’s part of your identity in all aspects of it: the psychological wellbeing, the physical wellbeing, the public persona, the private self. All of those things are bound up within your identity as an athlete. But this too shall pass.

Lex Gillette:

Yeah. So I started a speaker business probably a year and a half ago. So I’ve been doing that, which has been a lot of fun. I wrote a book last year and that released in April. I think that after I’m done with sport, I’ll certainly continue to run my business and continue to speak. I don’t envision myself in the eight-to-five job. And certainly nothing wrong with that, but I think that for the past 16, 17 years, I’ve literally been doing this since I was a teenager.

Aleks Krotoski:

Tell me a bit about Myles Monroe and how you discovered him.

Lex Gillette:

Myles Monroe is a lot of things. He’s a pastor. He’s a businessman. He’s a speaker philanthropist. I stumbled upon him because I had a… Mrs. Sherman is someone who I’ve known since I was three years old. She’s basically, besides my mom, she’s been through the entire journey with me in life, and she was a transition counselor. So she’s pretty phenomenal. And I’ll never forget, I’m not sure where we were coming from, but whenever I go back home to Raleigh, North Carolina, we’ll find time to meet up and we’ll go out to eat. And I want to say, we were sitting in the car and somehow she randomly asked me, have you ever heard of Myles Monroe? I’m in my room or something: “Oh man, Mrs. Sherman said I should look up Myles Monroe. Let me check this dude out.” So I get on YouTube. And immediately I’m listening to the titles of different videos. When I choose to click on them, he had one called Why People Need Visions And Dreams. And it was an hour and a half long. And I was like, “Man, this dude is powerful.”

Aleks Krotoski:

And here, of course we’re talking about the vision of not exactly foresight or strategic planning or just an imagining of who you are, not physical eyesight. Not vision in the biological sense.

Lex Gillette:

Right, yeah. Literally, what is it that you see for your life? What do you see beyond the horizon that your ability to see things before they exist? And I remember asking my friend, “Is it possible to have a mentor and not actually meeting this person in real life?”

Aleks Krotoski:

Because he died. He died not long after you discovered him, right?

Lex Gillette:

Yeah. It may be a year. He died in a plane crash. And that’s when I went on online. That’s when I knew the magnitude of who he was just from other people. Barack Obama was talking about him, and the T. D. Jakes of the world and just a ton of different people. I’m like, “Wow, okay.”

Aleks Krotoski:

You mentioned he’s a pastor, right? He’s also a speaker. So he knows how to use his voice. Can you describe that for me?

Lex Gillette:

His voice is very much just commanding. When you hear him, you listen. But he knows how to use his voice as an instrument. He knows when to put more emphasis on certain words, he knows when to back off and be more subtle or soft-spoken, and it makes the presentation really… I mean, it’s almost like an experience.

Aleks Krotoski:

The word vision here, yeah, as we’ve described, it does have a double meaning. And you said that the first things that really pulled you in, that you tripped into his world, use the word vision. Do you think that that was an important aspect of how you related to him? So for example, if he’d used the word dreams or possible selves, do you think that there would have been as much of a resonance for you?

Lex Gillette:

The video that really drew me to him, he talks about vision and he talks about how, if it’s something that you really believe in, then that vision should guide your actions daily. That’s what really caused me to gravitate towards him. And I say that because when I had lost my sight and I felt isolated and outside of “normalcy”, if you will, the one thing that bridged that gap and brought me back to reality is that everything centers around vision. You create a plan, a strategy, work relentlessly to bring that into fruition. And again, he just breaks it down and makes it so simple.

Lex Gillette:

And especially using the example of athletics, I want to win a gold medal. So it makes sense to have that discipline, to go down and train every day, having that discipline to eat the appropriate things, to make sure that you’re staying nourished and replenished and allowing your muscles to have the right things going inside of your body to help your muscles to grow and recover from hard workouts. And then, so circling back to Myles Monroe, it just felt like when I was listening to that video particularly surrounding vision, it was like, “Man, he’s speaking my language right now. This is resonating.”

Aleks Krotoski:

How often do you listen to his speeches? Do you listen to them when you’re low or when you need that reminder, or do you listen to them every quarter when you’re like, “Okay, now I need to do this in the next three months”? Is it a passion or is it a function?

Lex Gillette:

It varies. It varies, because sometimes I’ll listen to them every day. And then there’s been times where I’m like, “All right, well, I’m powered up. I’m good right now.” At this point, I think the last time I listened to a video was maybe a week or a week and a half ago, but I feel like it would certainly do some good in the next week or so to revisit that again. I’m about to begin to really start training hard and putting my body and mind through a lot of do a lot of hard work on this road to Tokyo. And I think it’ll do some good to revisit some of those things to get a refresher.

Aleks Krotoski:

I had a video that I watched when I was writing a book. I squirreled myself away to somewhere where there were no people, and I had internet connection and that was it. And I listened to this video every morning, just to get me going, to remind yourself. And this in particular was like, “Don’t get up and make a sandwich. Don’t clean your sock drawer. Sit down and just write the damn thing.” And it feels to me like that’s how you’re using these videos. You know the library. So you’re like, “This is a top-up.” This is part of your ritual, part of your routine.

Lex Gillette:

Yeah.

Aleks Krotoski:

I’m struck by the fact that as an elite athlete, as a global superstar athlete, you have that vision baked into your everyday life. How can everyday people who aren’t going to Tokyo in 2021… What do you see as a way others might find vision when it doesn’t have such a clear outcome?

Lex Gillette:

I think that we as people just have to start to stop comparing our visions to others. And it’s hard because as human beings, we’re creatures of compare and contrast. We look at what we do and compare it against what others are doing. But the reality of it is if that is your vision and it’s something that you wholeheartedly believe in, then that’s all you really need. It is your unique vision for life and vision for success. It means something. It may not look like a literal goal medal, but it is a gold metal because you saw it in advance and you did what you needed to do to bring it into reality.

Aleks Krotoski:

For more on Lex Gillette, go to lexgillette.com. For show notes and links to stories mentioned in this episode, go to standingontheshoulders.net. Standing on the Shoulders is a Storythings production. This episode was produced by Shruti Ravindran and it was edited by Ian Steadman. Our audio engineer and sound design is by Kenya Jay Scarlett, artwork by Darren Garrett, website by Eden Brackenbury. Our executive producers are Hugh Garry and Caroline Leary. It’s supported by Pearson and hosted by me, Aleks Krotoski. It takes a lot of time and a big team of people to make this podcast, more than most people would imagine. So if you like the show, please go to Apple Podcasts, Spotify or wherever you get your podcast fix, and rate it. It really does help people to discover us. That was the last episode that we had for this season. Thank you so much for listening, and we’ll see you next time.

Episode Credits

Standing on the Shoulders is a Storythings production.

Hosted by Aleks Krotoski

Written and produced by Shruti Ravindran

Audio engineer and sound design by Kenya Scarlett

Artwork by Darren Garrett

Website by Eden Brackenbury

Executive Producers are Caroline Leary and Hugh Garry

Supported by Pearson